Students moving from primary classrooms to a secondary timetable suffer from a kind of culture shock when their expectations of school are radically challenged by the pace and siloed structures of faculty education. Students may find school overwhelming, disorienting and alienating. Student engagement suffers and potentials for the development of life-long learning dispositions are diminished. Our two-tiered approach to schooling is sometimes a strange thing. Up until Year 6, we keep our kids together in one room, with a single teacher but from Year 7 on, we throw them into the timetable, mixing it in the locker bays and corridors of secondary school. We know that student engagement declines sharply as students enter secondary school, so perhaps it’s time for us to rethink the model and begin to explore ways to maximise schooling for students in the middle years.

Earlier this year, I travelled on a NSW Premier’s Teachers Scholarship to explore the opportunities presented by middle school models. I set out with the understanding that students in transition leave primary school with high levels of excitement and anticipation which they lose as they enter secondary school. NSW Government’s Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE) reports engagement in NSW students in three domains: students trying hard to succeed, positive sense of belonging and students who value school outcomes. For students up to Year 6, all three descriptors report at levels between 80 and 100 per cent. From Year 7 onward these figures drop off at an alarming rate, reaching their nadir in the low 60 per cent at around about Year 9. This is perhaps not so surprising to anyone who has taught Year 9 classes, but frighteningly, the engagement levels do not return significantly by Year 12.

In the United States, middle school models bridge the transitional years, and this may have some lessons for Australian educators. The middle school model acknowledges that between Years 5 and 8, students undergo some of their most prolific changes. Michael Giles of Colorado’s Cherry Creek School District dubbed middle schoolers as “the range of the strange”. The dominant features of student profiles within the ‘range of the strange’ are a sense of alienation and at times disconnection, unexplained change, a need to be directed and an emerging need to direct oneself. Standardised curricula tend to assume a level of homogeneity in students, so the variability within middle years students presents a significant challenge to educators. In Australia we manage it by splitting the group into primary and secondary cohorts, treating one group as children and the other as grownups. Alternatively, middle school systems recognise that there is a range of developmental profiles or continuum in which students may some days behave as grownups and some days not. The agenda shifts significantly in favour of developing schools that respond to the range, meeting students where they are in this tricky period of life. Middle schools succeed by implementing strong social and emotional learning agenda that aim to contextualise learning locally, help students to make wider links and foster a strong sense of agency within students who come to see that they have a right to belong in their school.

At Farnsworth Middle School, Albany NY, the principal, Dr Mike Laster explained that the school was committed to teaming of classes and students, developing a deep sense of belonging for all students and fostering relationships with trusted and trusting adults. Teaming of classes partnered groups of students with a pair of teachers, the effect was that students now had two ‘go to’ adults able to respond in a variety of ways to students. Teaming also allowed for a variety of class configurations, groupwork and expansion of access to teacher perspectives, interest and skills.

Farnsworth MS set three goals for teacher development.

- Instructional technology

- Cultural responsiveness

- Health and well-being

The three domains all led to the development of student engagement, belonging and relevance as the touchstones for including the wide range of student profiles. At Farnsworth, there was an emphasis on recognising the developmental challenges faced by students in the middle years of school. Reading the walls, it was clear that student behaviours were to be developed, not managed. Belonging as a value was prominent, positive attitudes such as personal agency, consideration of others, teamwork, honesty and positivity were important attributes.

In Atlanta, The Ron Clark Academy not only set out an agenda for belonging, but also for high energy and high achievement. Clark made his name off the back of the New York Times best seller, The Essential 55, a series of rules that promote mannered relationships, social courtesies, personal responsibility and dignity.

Teaching at RCA is a balance and blend of structure, discipline and respect with creativity, passion and enthusiasm. RCA fosters and captures high energy and enthusiasm of students within the middle school age range. Clark’s methods include a high degree of interpersonal engagement through conversational and expositional protocols, songs, dances, student movement, energetic teaching and frame breaking behaviours, most notably walking on desks and moving through different physical levels and platforms in the classrooms.

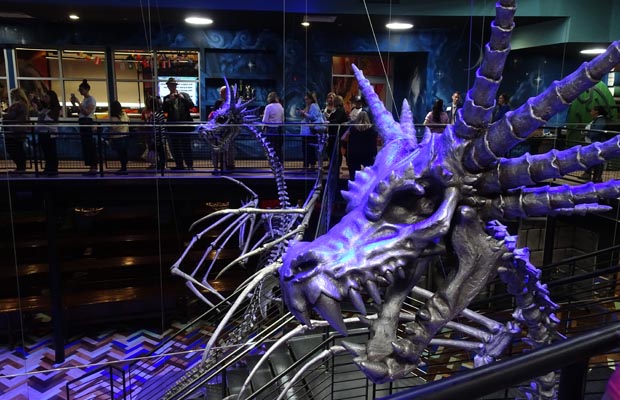

The campus at RCA is clearly all about the students. This is a school that looks and feels like a fun place to be. The exterior is built to look like a fantasy castle, its nods to Harry Potter and Tolkien’s fantasy-scapes are obvious and the huge dragon that flies expansively over the basketball arena and gathering hall is spectacular, as is the two-storey dragon skeleton that dominates the stairwell in the main building. Each of the rooms in the RCA is painted, decorated and lit in ways that reflect the most interesting aspects of the disciplines. The science room is designed as a mad scientist’s lab; the reading room is themed after Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland. The history room reframes dominant narratives, depicting the civil rights history of the South, and in the language arts space, superheroes abound. Loud music, props and lizard tanks all add to the atmosphere of RCA. It is a school that is democratic in nature, empowers kids and communities, and develops agency while its values work to develop essential elements of character and efficacy in the students.

The Ron Clark Academy is truly unique, and sometimes it seems that emulation is insurmountable. That shouldn’t be a barrier to the development of new and better school models or contexts. New York City’s St Stephens of Hungary is a pre K to Year 8 school that has been educating kids on the upper east side for over 90 years. This is a school that operates very much in the traditional mode of schooling. Here they make use of a continuum of developmental responsiveness to the different ages and stages of its school cohorts. Students moved through a range of class configurations. The school develops approaches appropriate to groups of connected year levels. Up to the Third Grade, students are taught in contained classes, with one teacher taking them through the common core. In Fourth and Fifth Grades some specialisms begin to emerge in combinations of Maths and Science, or English Language Arts (ELA) with Religious Education or Social Studies. By grades Six, Seven and Eight, students transition to the familiar faculty or department-based model found in most high schools. School leader, Jenn DeSpirito, recognised the mix of student emotions, dispositions, outlooks and self-identities made the observation that having a broad mix of K-8 allowed for students to enjoy the moments of being kids rather than racing forward. Grade Eight kids were still happy to take part in the dress-ups and play of festivals like Halloween because they were still close to the younger students. Recognition of the middle years as a stage of its own allowed for students to step in to and out of their emerging identities.

Students entering into adolescence embark on a journey fraught with challenge, change, setback and success. It is a time of massive development, and one that may set patterns of learning and experience that can frame a lifetime. Many schools and teachers set teaching and learning goals that foster life-long learners, but the CESE study shows that something in our current approach is not delivering that outcome. The two-tiered system sets up two groups of students; one that remain as ever children, and one that throws our students headlong toward adulthood. Maybe a middle approach will help to develop schools that can respond to students who are in a state of flux, simultaneously rushing forward, while seeking bonds and anchors to the nurturing securities of the known. Maybe it’s time we built a middle school system.

Shane Giles is assistant principal, Learning Enrichment, at Lumen Christi Catholic College in NSW and a recipient of the 2019 Premier's Curriculum Transition Scholarship.

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Education Review The latest in education news

Education Review The latest in education news

Thank you for this article. If you are even in Canberra, please come and visit our middle school at Burgmann Anglican School. We don’t have dragons and castles, but we do have a vibrant middle school that strives to achieve many of the outcomes you have written about.